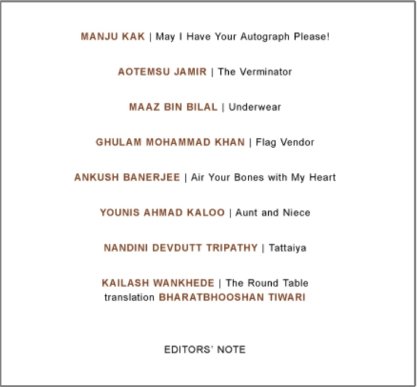

In this edition, we feature nine stories. They are:

The Rain by Rajalakshmi N Rao

All that We See or Seem by Vrinda Varma

Remains Of Self: The Story of a Fundamentalist by Manju Kak

The Cure by Amita Basu

The Portrait by Pravin Vemuri

The Womb by Ashwini Shenoy

Chapter Six of Roohi Choudhry’s recently released novel, Outside Women

Shiuli by Ratul Ghosh

The Kindness of Strangers by Avishek Parui.

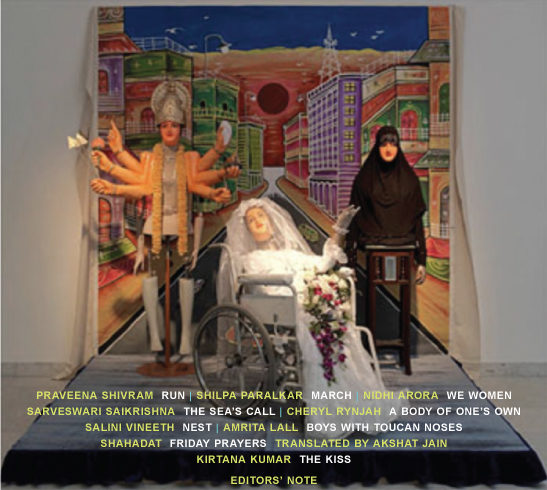

Artwork - ISSUE 57

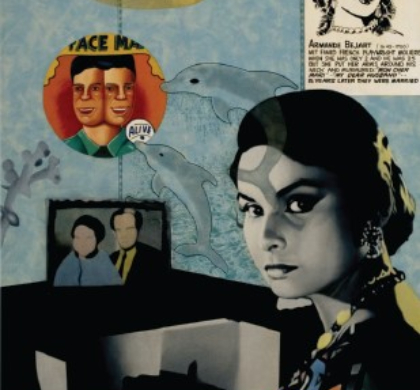

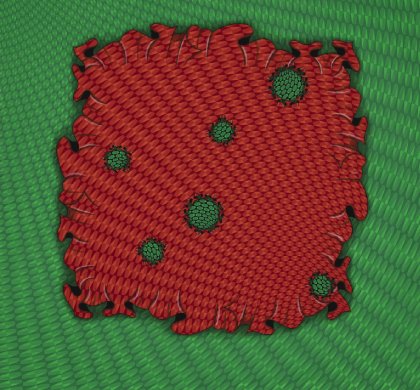

‘Fly’ by Vivan Sundaram, from the series, ‘Trash’, 2008.

Courtesy the estate of Vivan Sundaram.

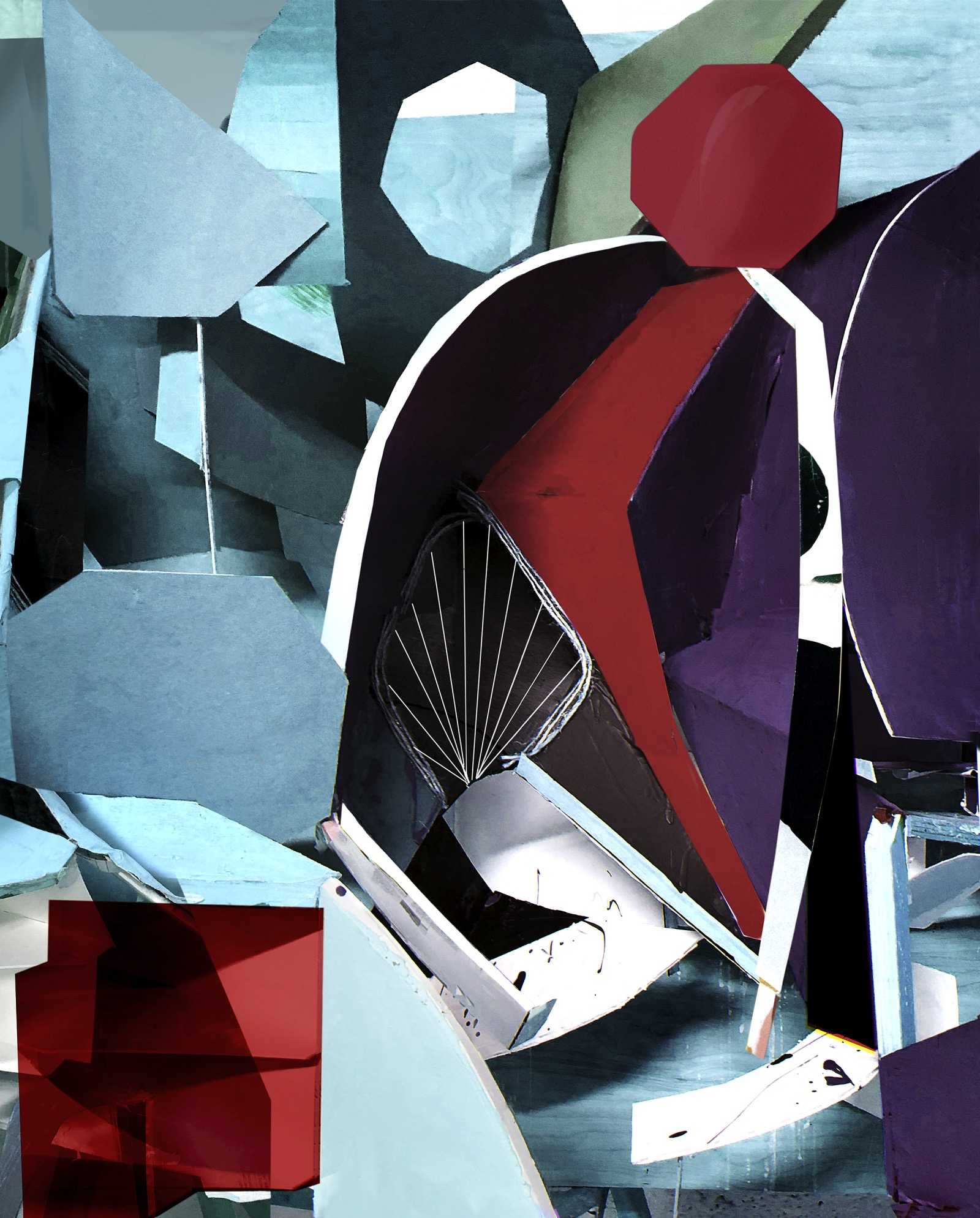

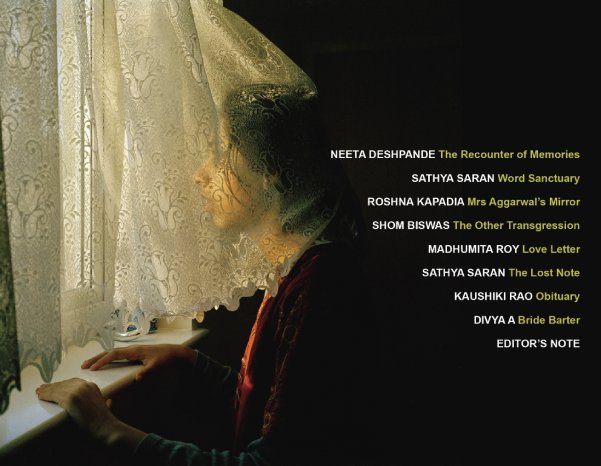

Artwork - ISSUE 56

‘Silhouette’ by Yamini Nayar, from the series, ‘If stone could give’, 2019.

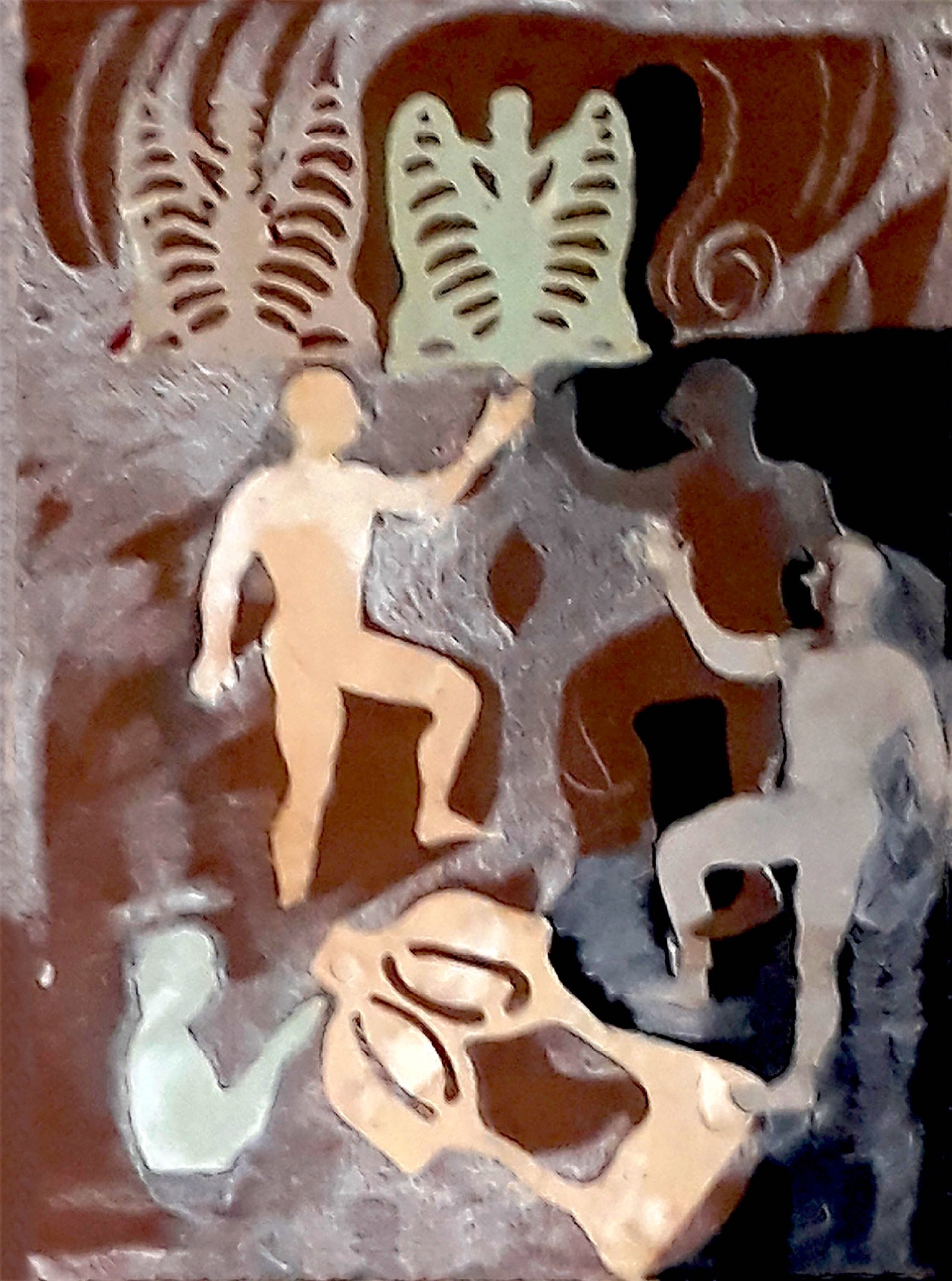

Artwork - ISSUE 55

‘Bodies Cutout’ by Bharati Kapadia, from a wall installation created for the film ‘How Do I show the Ocean Space You Carried Inside You?’, 2022.

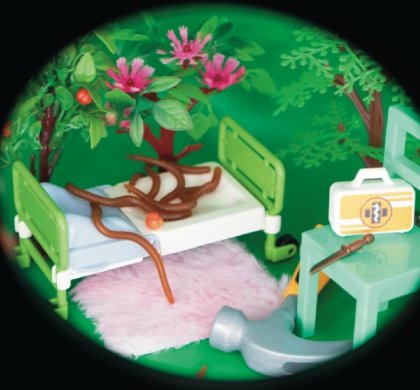

Artwork - ISSUE 54

‘Inside and Out – Wormendectomy’ by Mira Brunner, photocollage, 2024.

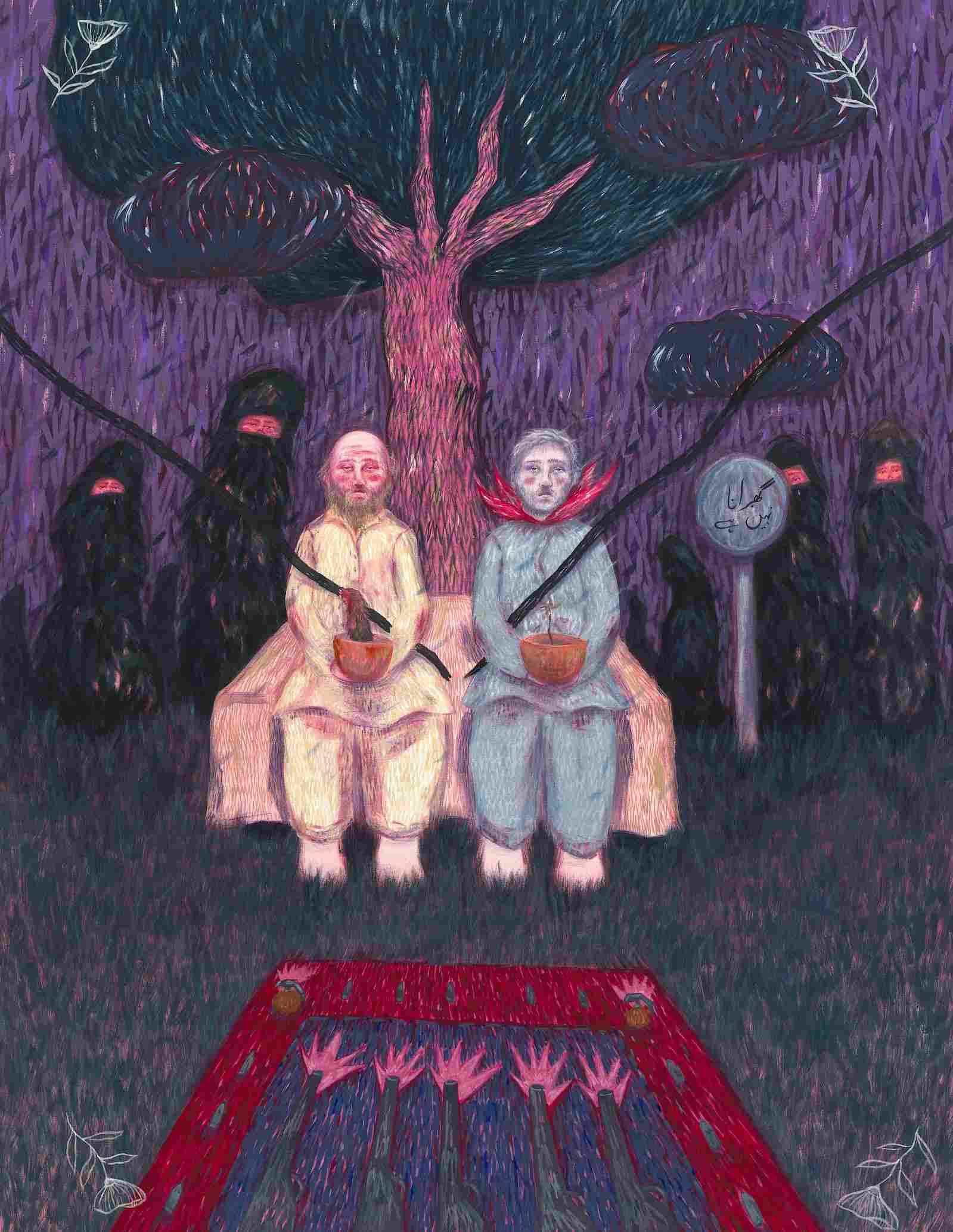

Artwork - ISSUE 53

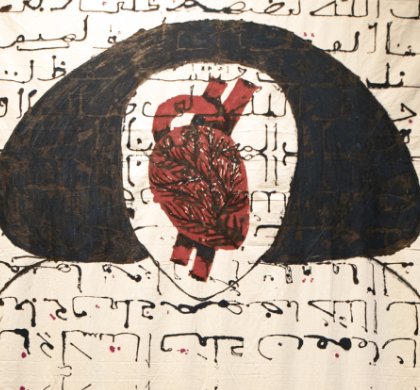

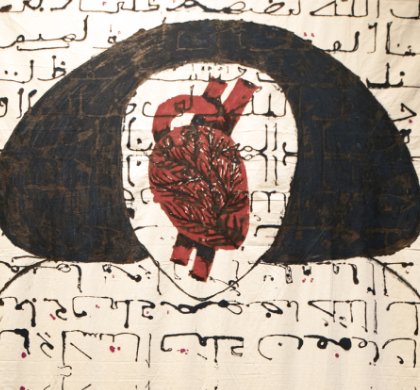

‘An-Nisa 1’ by Arshi Irshad Ahmadzai, ink on kora fabric, 152 x 119 cm, property of the artist, 2019, painted at the 1 Shanti Road Studio, Bangalore.

Artwork - ISSUE 52

In this issue, that marks the transition to a new website, the stories are presented on a plain white background thus showcasing the original cover design by Yamuna Mukherjee.

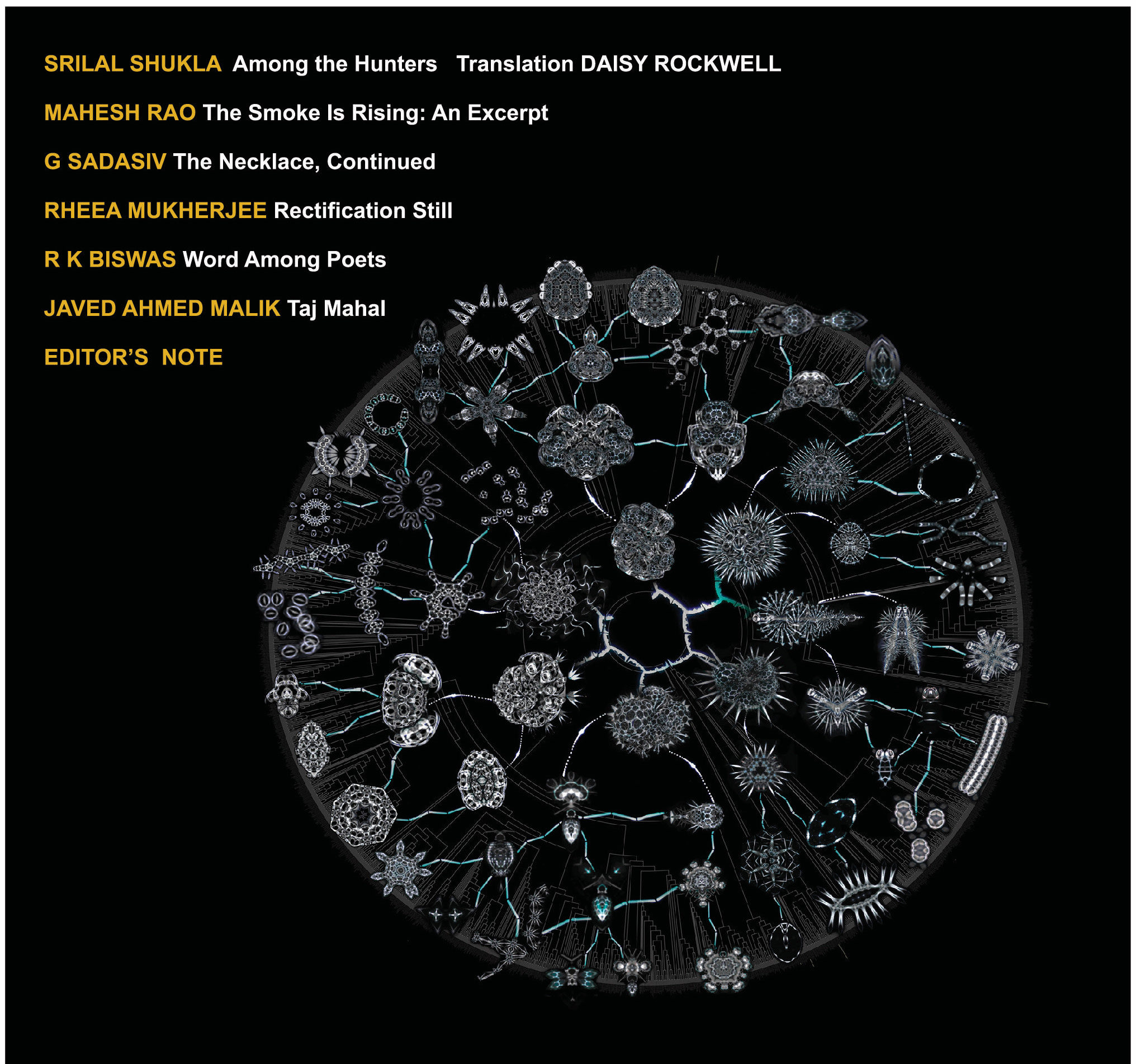

Artwork - ISSUE 51

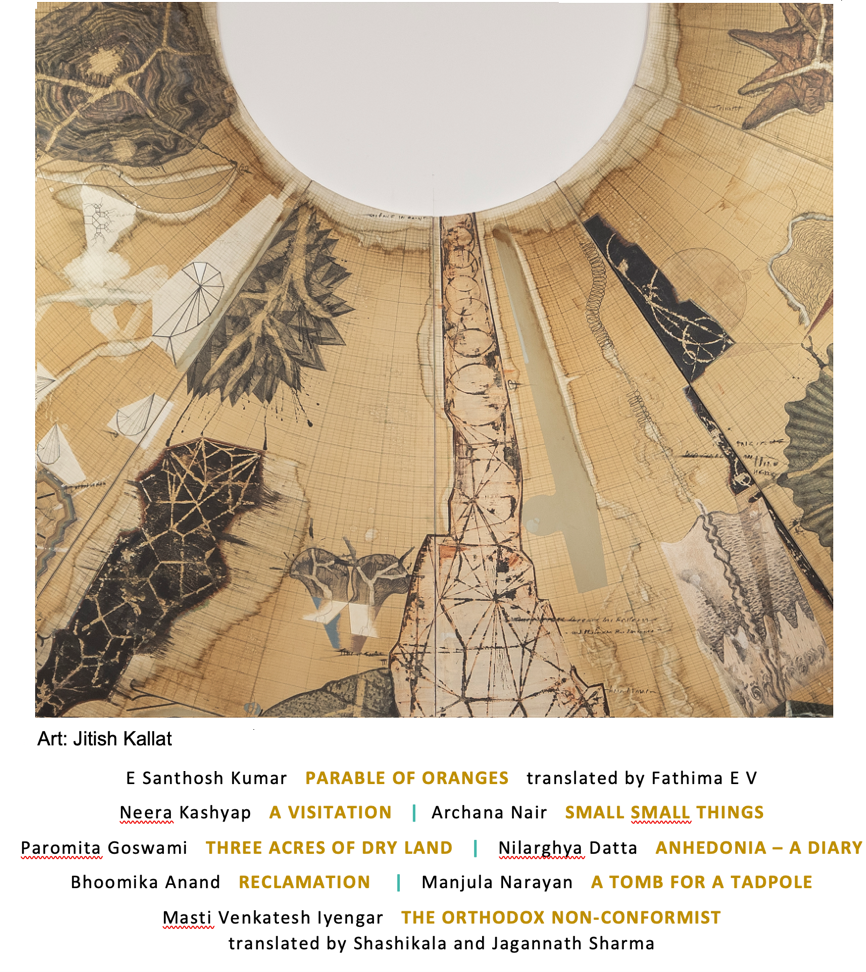

The cover art is a detail from ‘Postulates from a Restless Radius, 2021’ by Jitish Kallat, details of which are as follows: Acrylic, gesso, lacquer, charcoal and watercolour pencil on linen, 640 x 320 cm radius, 375 cm length, Installation view, Ishara Art Foundation, UAE.

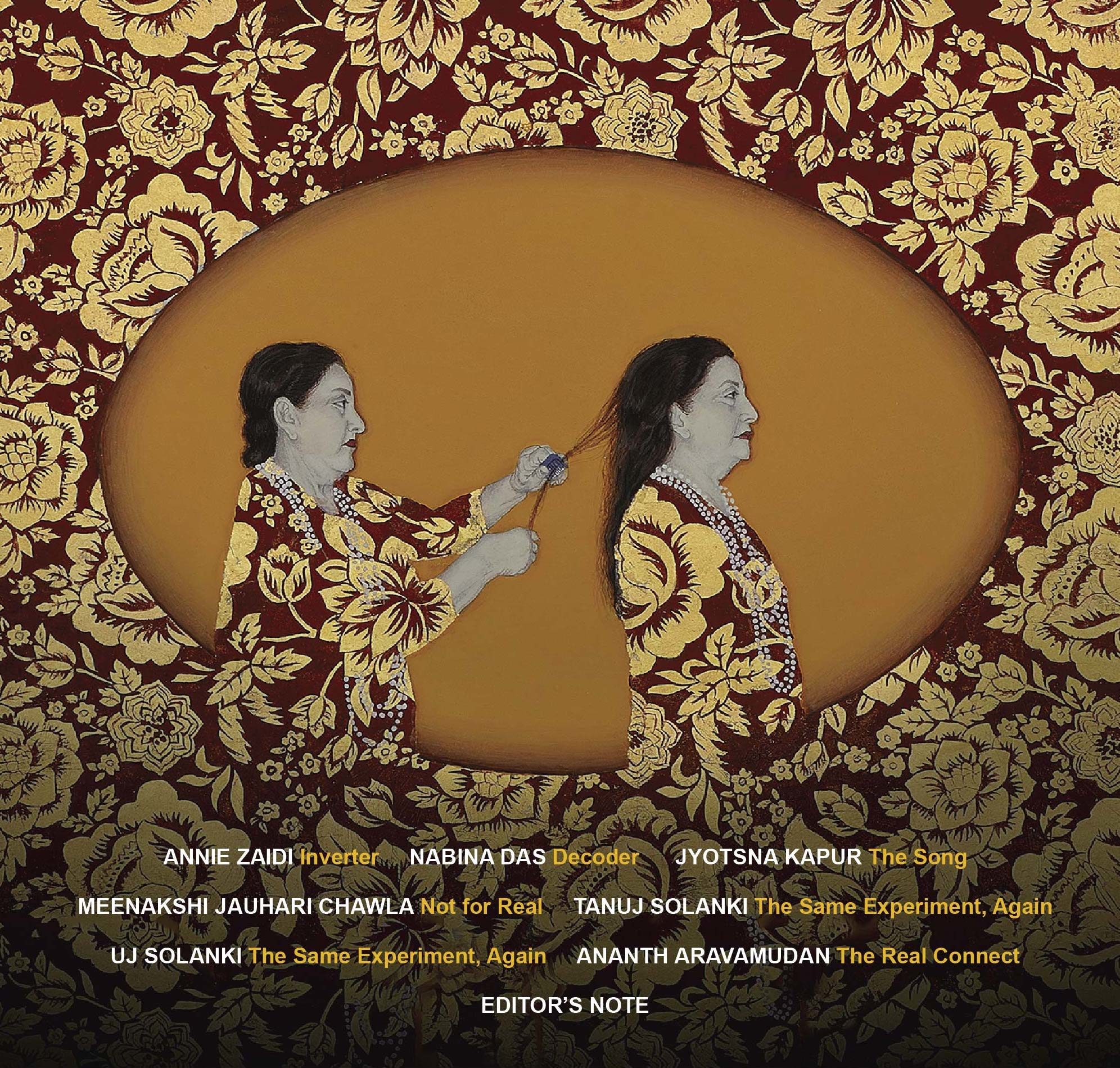

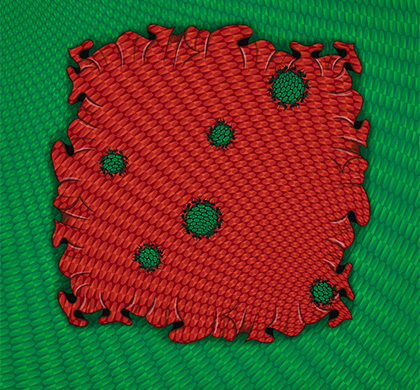

Artwork - ISSUE 50

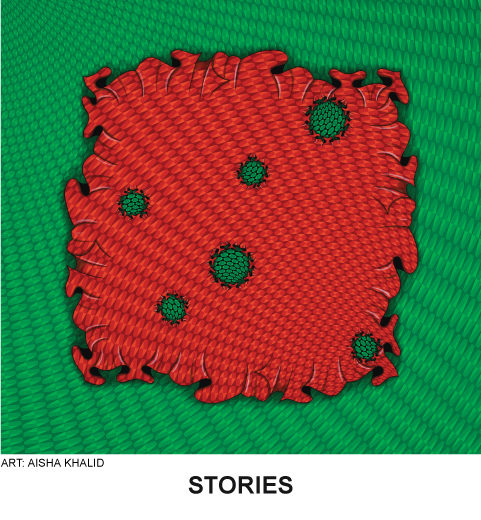

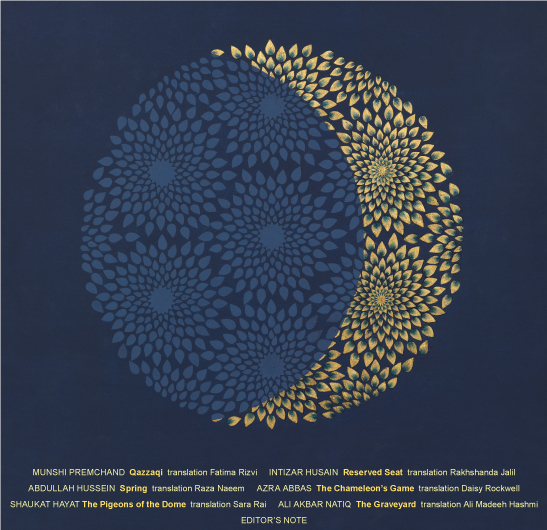

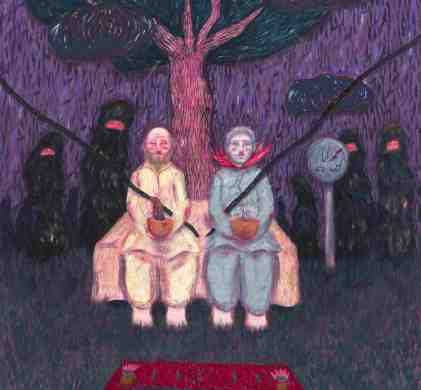

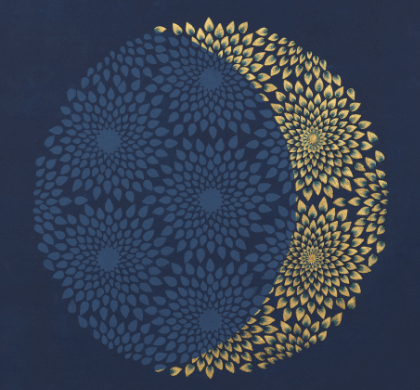

The cover art is by Aisha Khalid from the series ‘Fling Me Across the Fabric of Time and the Seas of Space’, gouache on paper board, 2022, 121.9 x 121.9 cm

Artwork - ISSUE 49

The cover art is by Pushpamala N, titled Triptych, 2013, where three mannequins representing three major Indian communities pose against a painted street scene, diorama with painted sets, mannequins, costumes and props, size 8 x 8 x 6 feet.

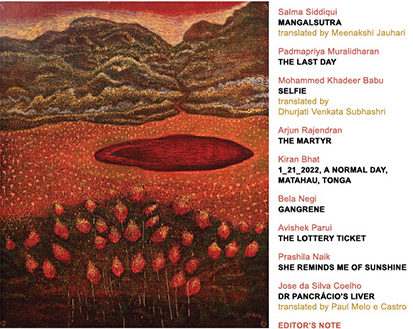

Artwork - ISSUE 48

The cover art is by Soghra Khurasani, titled Land-Escapes, 2015, Woodcut Print on Paper, 48 x 40 inches, in an edition of 3.

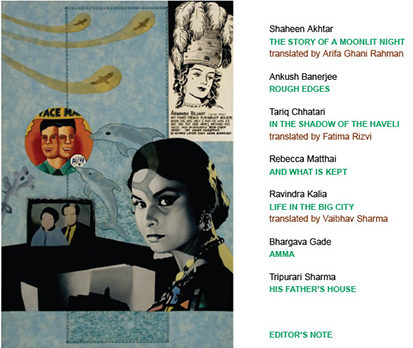

Artwork - ISSUE 47

The cover art is by Atul Dodiya, titled ‘Karuna’, 2004-2006, 72 x 48 inches, enamel paint and synthetic varnish on laminate. Atul Dodiya was born in 1959 in Mumbai.

Artwork - ISSUE 46

The cover art by Gauri Gill bears the caption Untitled (15), from the series Acts of Appearance (2015—ongoing). Copyright Gauri Gill.

Artwork - ISSUE 45

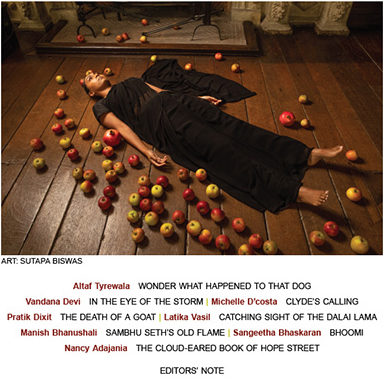

The cover art is by Sutapa Biswas and is from Lumen, 2021. Still. Digital video mastered on 4K. Duration: 30 minutes. Colour with sound. © Sutapa Biswas. All rights reserved, DACS 2022. Government Art Collection, UK.

Artwork - ISSUE 44

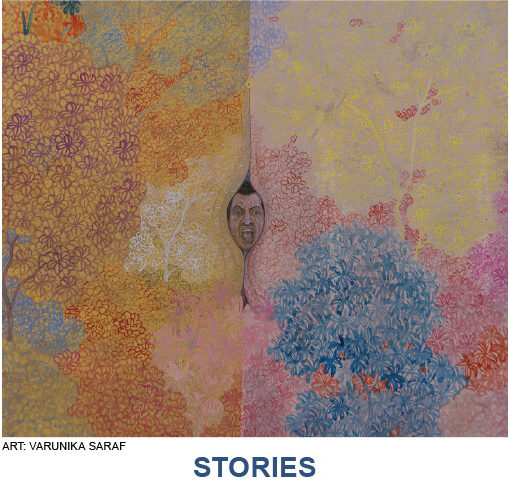

The cover art is by Varunika Saraf and is part of her recent body of work, Caput Mortuum of which she says in her catalogue, ‘To speak about a present besieged by brutal acts of violence, this body of work takes its name from the synthetic Iron Oxide pigment Caput Mortuum (Dead Head) that resembles dried blood.’ The image is a detail from the work ‘Let’s Tell it Like it Is’, 2020, watercolour on Wasli backed with cotton textile, 67 x 76 in.

Artwork - ISSUE 43

The cover art is by Lubna Chowdhary and is one of the series of three ceramic works titled ‘Sign’, 140 cm x 140 cm, ceramic.

Artwork - ISSUE 42

The The cover art is by Alka Dass and is titled ‘The look you gave me made flowers grow in my…’, 2020, digital print, 14 x 14 cm.

Artwork - ISSUE 41

The cover art is by Alyina Zaidi and is titled ‘The Dark Valley – The Cave’, 20 x 16 inches, acrylic on wood.

Artwork - ISSUE 40

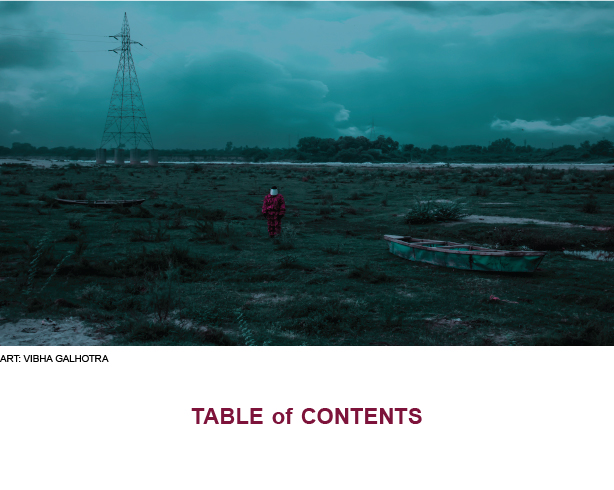

The cover image, is by Vibha Galhotra from the series IN … TIMES (performance photo work), digital photo print on Hahnemuhle archival paper, 2020; credits: collaboration on dress design – Rohit Gandhi + Rahul Khanna, behind camera – Rajesh Kumar Singh

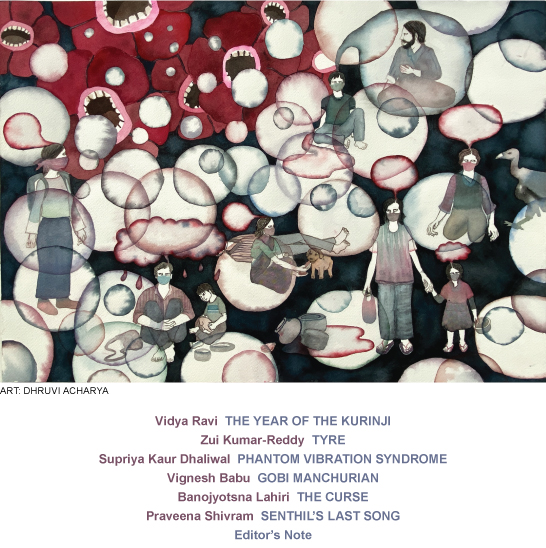

Artwork - ISSUE 39

The cover image for this release of Out of Print is by Dhruvi Acharya. Titled ‘Painting in the Time of Corona, 11 April 2020, lockdown day 18’ (watercolour on paper, 50.8 cm by 36.2 cm), it is one of an extraordinary series that she began on March 22, 2020, the day of the Janata Curfew. By that time, Dhruvi had been in self-isolation for ten days. She soon challenged herself to try and complete a painting every day of lockdown. Each of the pictures is visually compelling and profoundly thought-provoking, an intense reflection of what she is going through, what we are collectively going through. The one on the cover, with its layered complexity and multiple stories struck us as a way to look from the bizarre reality of the present time to a set of tense, strong stories written before the pandemic.

Artwork - ISSUE 38

The cover image ‘Rupture’, 2015, genuine gold leaf, site specific intervention Shyam Bazaar, Dhaka is by Ayesha Sultana.

Artwork - ISSUE 37

Issue 37, start Editor’s Note at : Out of Print 37 …

Artwork - ISSUE 36

The cover image by Rekha Rodwittiya is entitled ‘Love Done Right Can Change the World’, acrylic and oil on canvas, 1.83 m by 1.22 m

Artwork - ISSUE 35

The cover image entitled ‘Don’t Wait for Anything’, acrylic on canvas, 250 x 280 cm is by Laco Teren.

Artwork - ISSUE 34

Nilima Sheikh’s exquisitely detailed ‘Departure’, tempera on Sanganer vasli paper is reproduced with the permission of the artist.

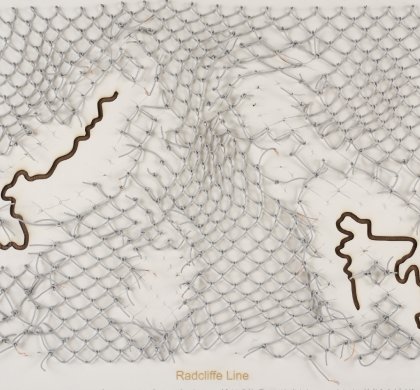

Artwork - ISSUE 33

The artwork by Reena Saini Kallat is titled the ‘Leaking Lines (Radcliffe Line)’, 2018, (electric wires, steel nails, charcoal, embossed and laser cut arches paper, 70 x 95 cm, image courtesy: Iris Dreams) and is reproduced with the permission of the artist.

Artwork - ISSUE 32

The artwork, untitled, mixed media, 60″ x 60″, is by Mehli Gobai. We are grateful to Shireen Gandhy for facilitating the use of the image that we have courtesy the late Mehlli Gobhai and Chemould Prescott Road.

Artwork - ISSUE 31

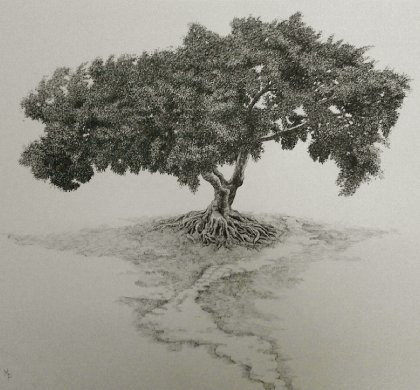

The artwork, ‘Tree and Trail’, pen and ink on paper, 14.5″ x 17″, collection of Nova and Jarvis Rockwell is by Michelle Farooqi.

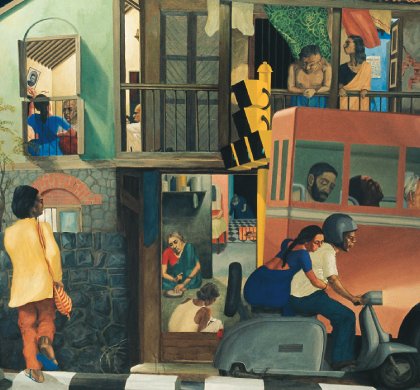

Artwork - ISSUE 30

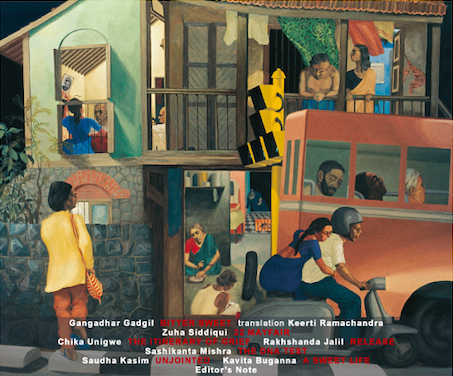

The artwork is by Sudhir Patwardhan and is titled ‘Street Corner’, oil on canvas, 1985, 152×183 cm.

Artwork - ISSUE 29

The cover image by Neha Choksi is the third panel from a series of 7 woodcuts, Repeat Integrity (Oak), 47 x 35 inches each panel, unique series, 2016. Photo credit: Anil Rane.

Artwork - ISSUE 28

The cover image by Olivia Fraser is one from a series of nine panels titled, You are the Sun, 2015, stone pigment, gold leaf and gum arabic on handmade Sanganer wasli, 14×14’’. Other panels from the series accompany the stories in the issue. The complete series, in sequence, may be viewed on the artist’s site.

Artwork - ISSUE 27

The image by Dhruvi Acharya, is of a 2010 10”x10” work of polymer paint on panel titled ‘He He He’.

Artwork - ISSUE 26

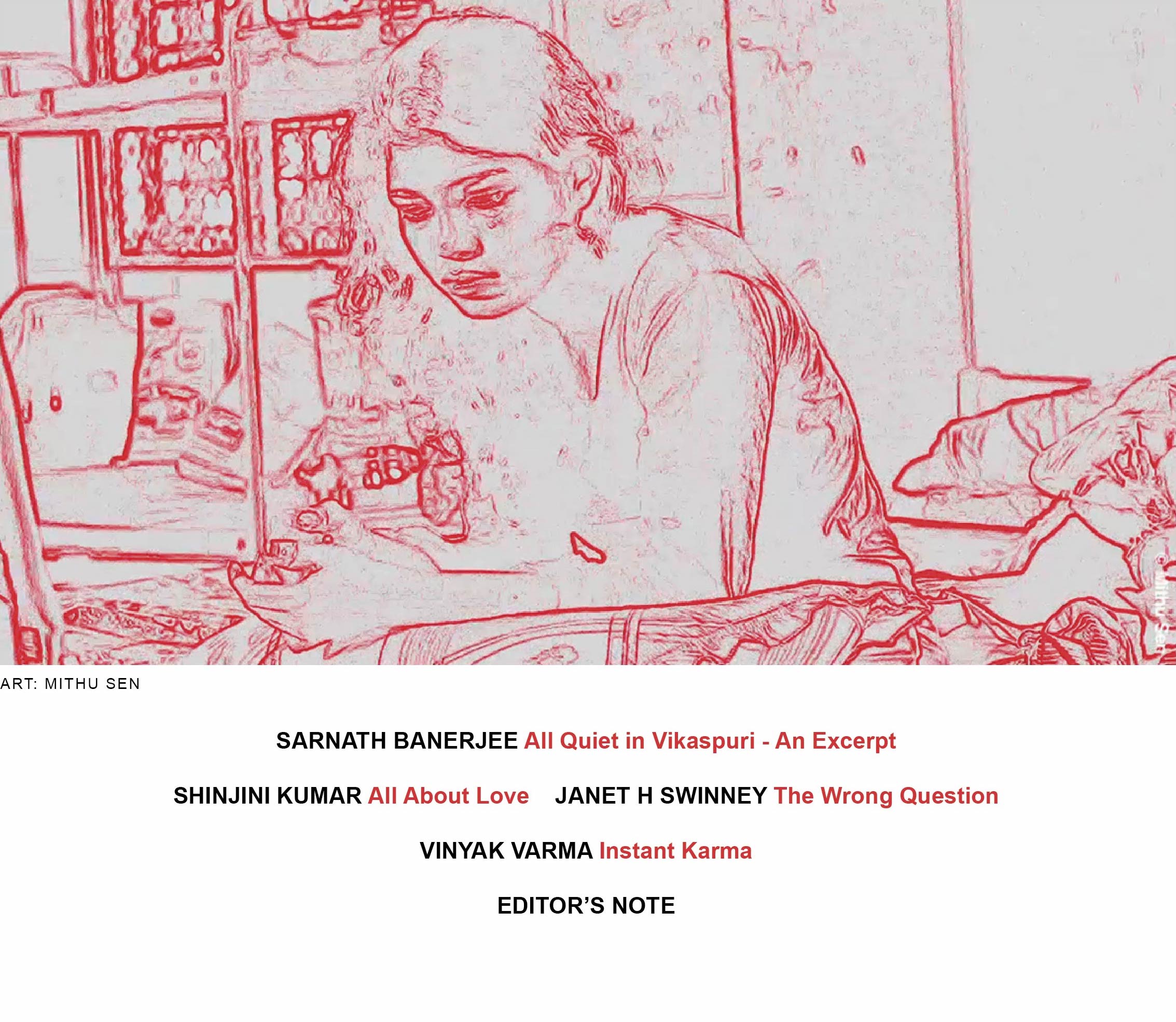

The image is a still from Mithu Sen’s 2014 Kochi Muziris Bienalle video installation I Have Only One Language; It Is Not Mine.

Artwork - ISSUE 25

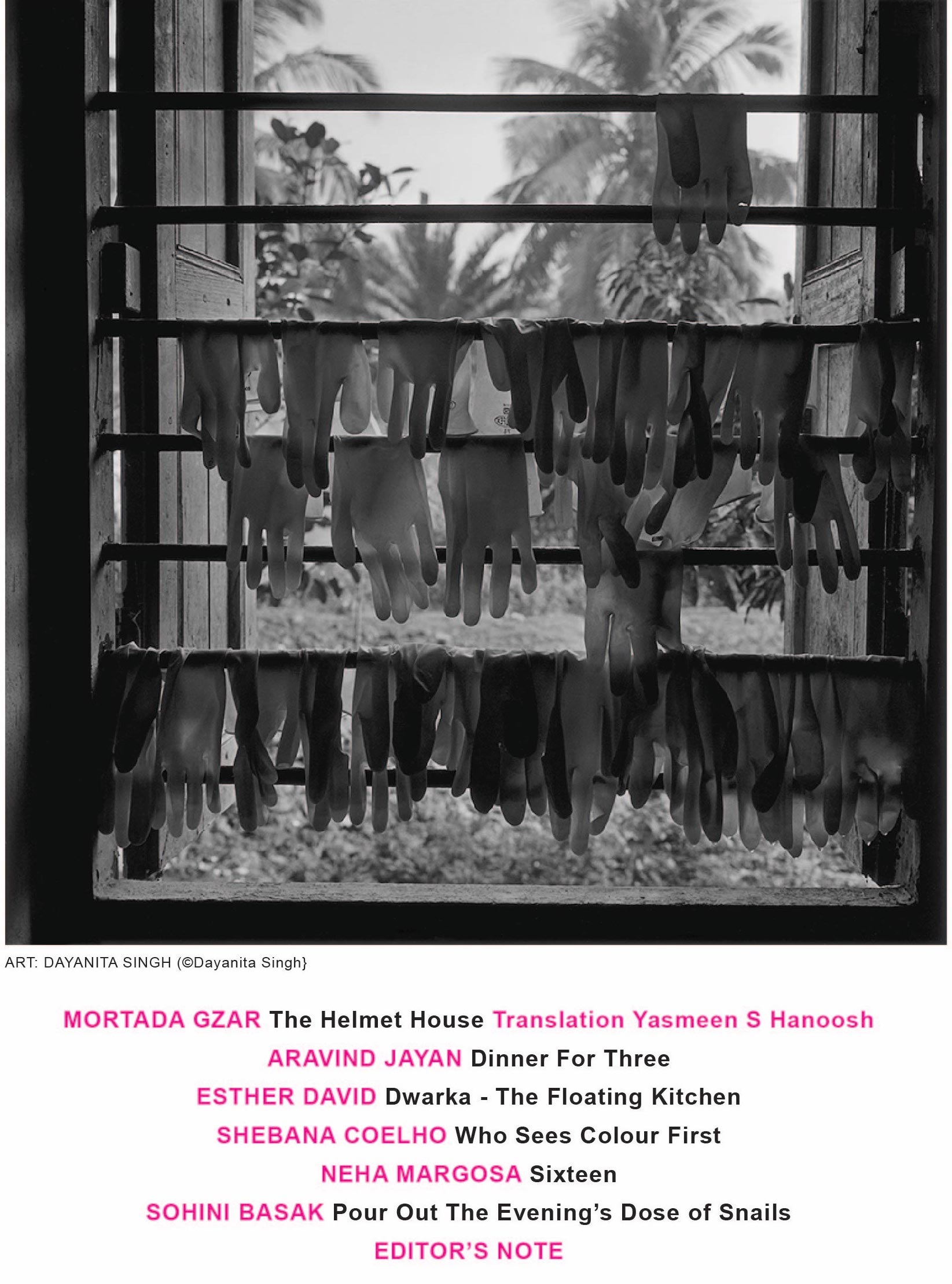

The artwork by Dayanita Singh is from her series, Go Away Closer. Termed ‘a novel without words’ the project ‘concerns a series of opposites’ such as ‘presence and absence’ and ‘proximity and distance’.

Artwork - ISSUE 24

The artwork by Anish Kapoor, Untitled, is a gouache from a leporello book made by the artist in 2011.

Artwork - ISSUE 23

The artwork is by Ranjeeta Kumari and is titled Afternoon (water colour on paper, 14”x 20”, 2016).

Artwork - ISSUE 22

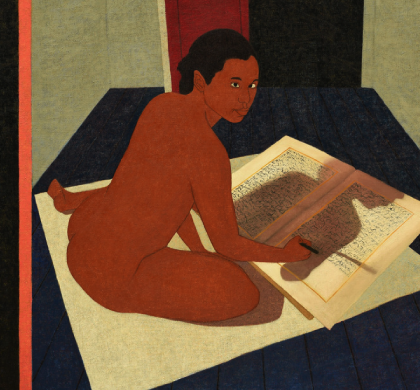

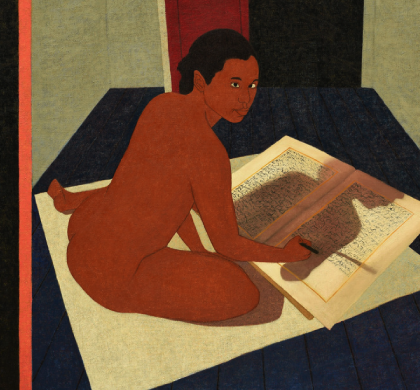

The artwork is by Mequitta Ahuja and is titled Performing Painting: Seated Scribe (oil on canvas, 84”x80”, 2015).

Artwork - ISSUE 21

The artwork is by Delna Dastur and is titled Balancing Act, (charcoal and pastel on canvas, 2008, 40×40’’).

Artwork - ISSUE 20

The artwork is by Sudhir Patwardhan and is titled Paying the Bill, acrylic on canvas, 2005, 36×48’’.

Artwork - ISSUE 19

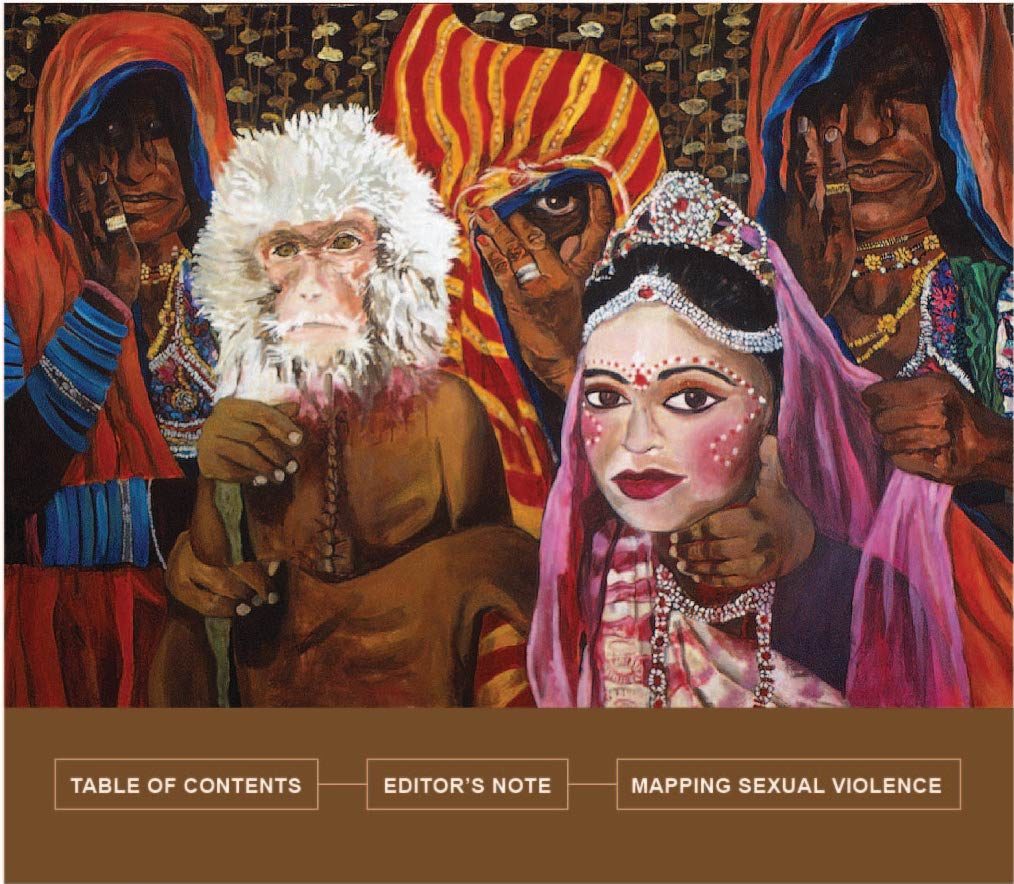

Artwork - ISSUE 18

The cover art by Chitra Ganesh is entitled Wedding Night (2000, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 66 inches).

Artwork - ISSUE 17

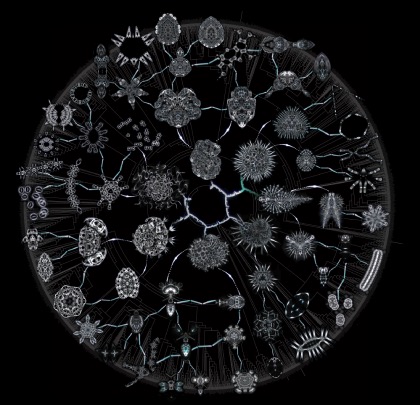

The artwork by Mira Brunner titled Cosmogram 4 was commissioned specifically for the issue.

Artwork - ISSUE 16

The artwork by Heraa Khan adheres in extraordinary serendipity to the thread of connection that runs through the stories in the issue.

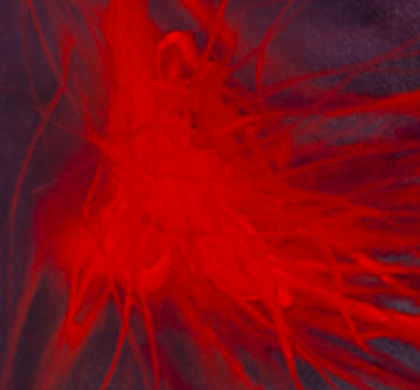

Artwork - ISSUE 15

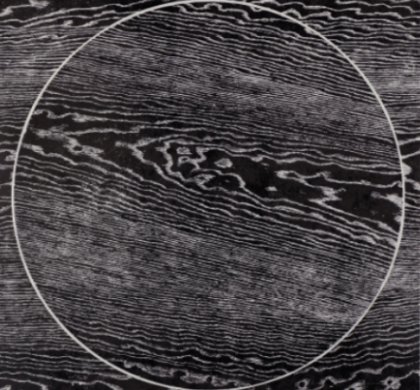

The artwork on the cover page by Rohini Devasher is a detail from her work Bloodlines, a video and print installation (single channel video, duration 45mins; print 60x60inches on Hahnemühle FineArt Baryta paper; 2009; image courtesy Rohini Devasher and Project 88 Mumbai).

Artwork - ISSUE 14

The artwork, entitled Underfoot and Overhead, is by Yamini Nayar and takes its name from a line of Rudyard Kipling poem entitled A Song of the White Men.

Artwork - ISSUE 13

The artwork, titled Searching for Rousseau is by Yamuna Mukherjee.

Artwork - ISSUE 12

Artwork by Suki Dhanda from the series, Shopna,

Artwork - ISSUE 11

Artwork, by Archana Hande, is from a sequence of the story board for an animation film, All is Fair in Magic White, 2009, and is rendered in acrylic, colour pencil, and charcoal pencil on cotton fabric of dimensions 3.5′ x 3.5′. The piece is a satirical account of an aspiring, tumultuous, dirty and shockingly populated Bombay and its hope for a picture-postcard conversion into a global megapolis of the future. Historicity complicates this troublesome vision by raising questions of power, class and race.

Artwork - ISSUE 10

‘Dawn’ by Olivia Fraser, stone pigments and Arabic gum on handmade Sanganer paper, 91.4 x 91.4 cm, 2012.

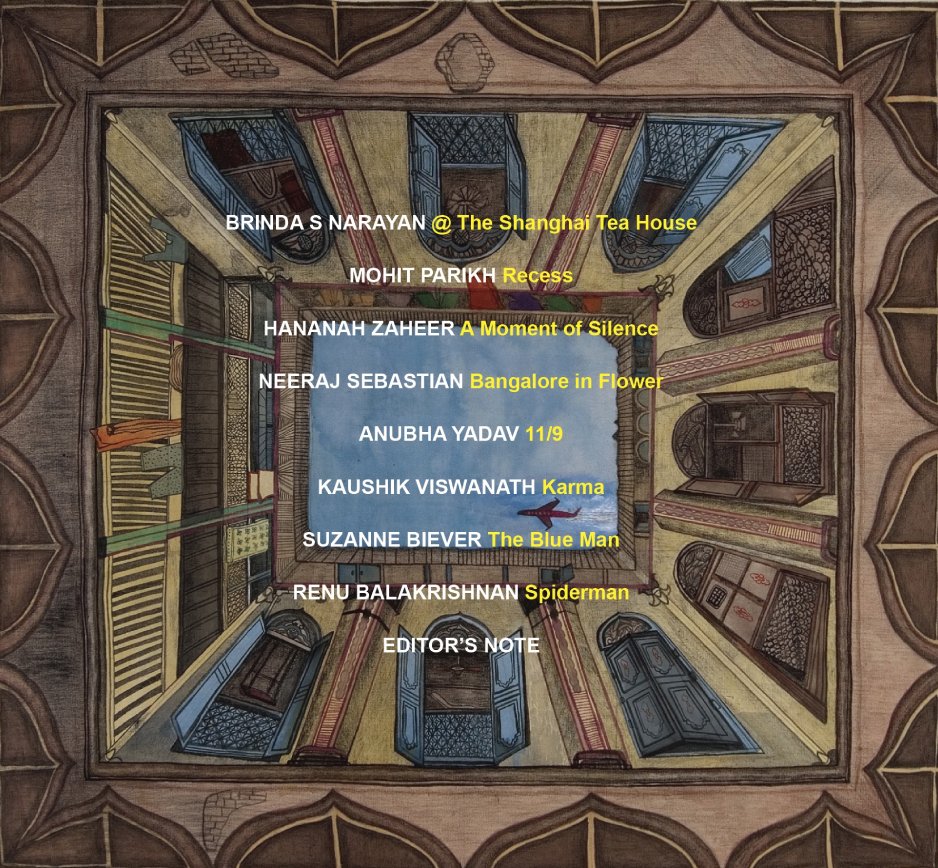

Artwork - ISSUE 9

‘Ambitions and Dreams’ by N S Harsha, from a collaborative community project involving the TVS School in Tumkur, cotton cloth, wheat gum, rock, size of each shadow – 6 m, 2005.

Artwork - ISSUE 8

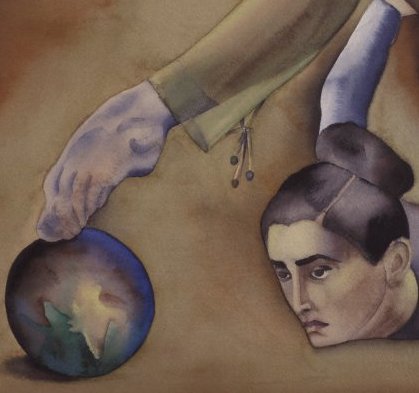

‘The Difficulty’ by Anju Dodiya, watercolour on paper, 55 x 74 cm, 1997.

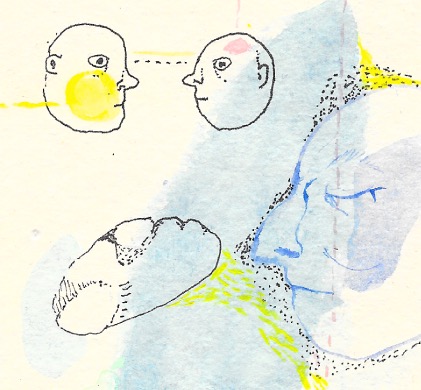

Artwork - ISSUE 7

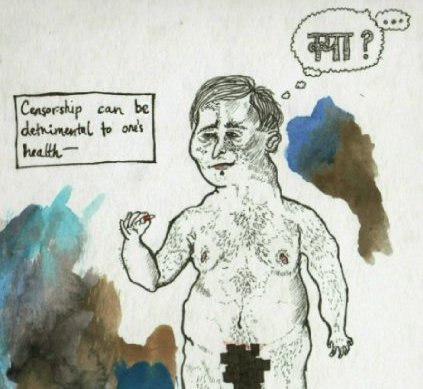

‘Kya’ by Out of Print editor, Mira Brunner, commissioned by Out of Print, Aquarelle on Aurangabad paper from Bombay Paperie, 2012.

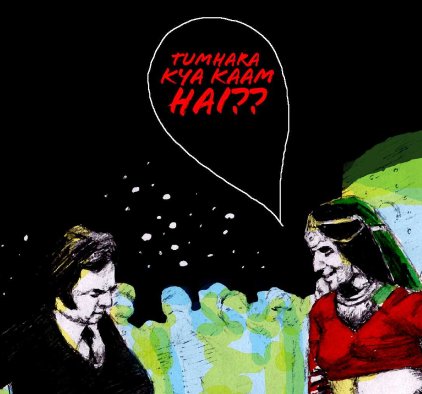

Artwork - ISSUE 6

‘Tumhara Kya Kaam Hai’ by Vinayak Varma, a hand-drawn re-purposing of a frame from Amitabh Bachchan’s ‘Mere Angane Mein’ song from the 1981 film, ‘Laawaris’, commissioned by Out of Print, 2011.

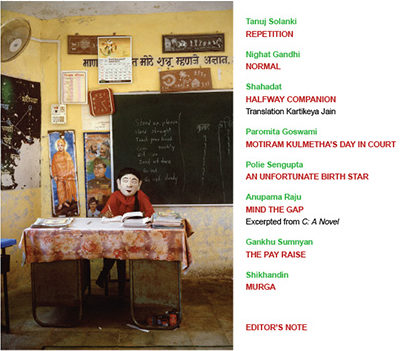

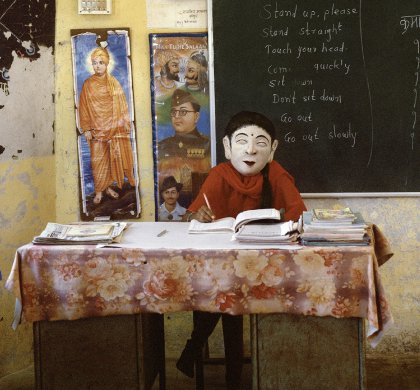

Artwork - ISSUE 5

The typeroom in the Finance Department of the Old Secretariat in Patna, Bihar from the Bureaucratics series by Jan Banning.

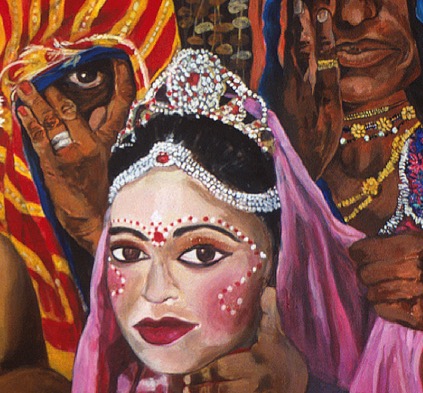

Artwork - ISSUE 4

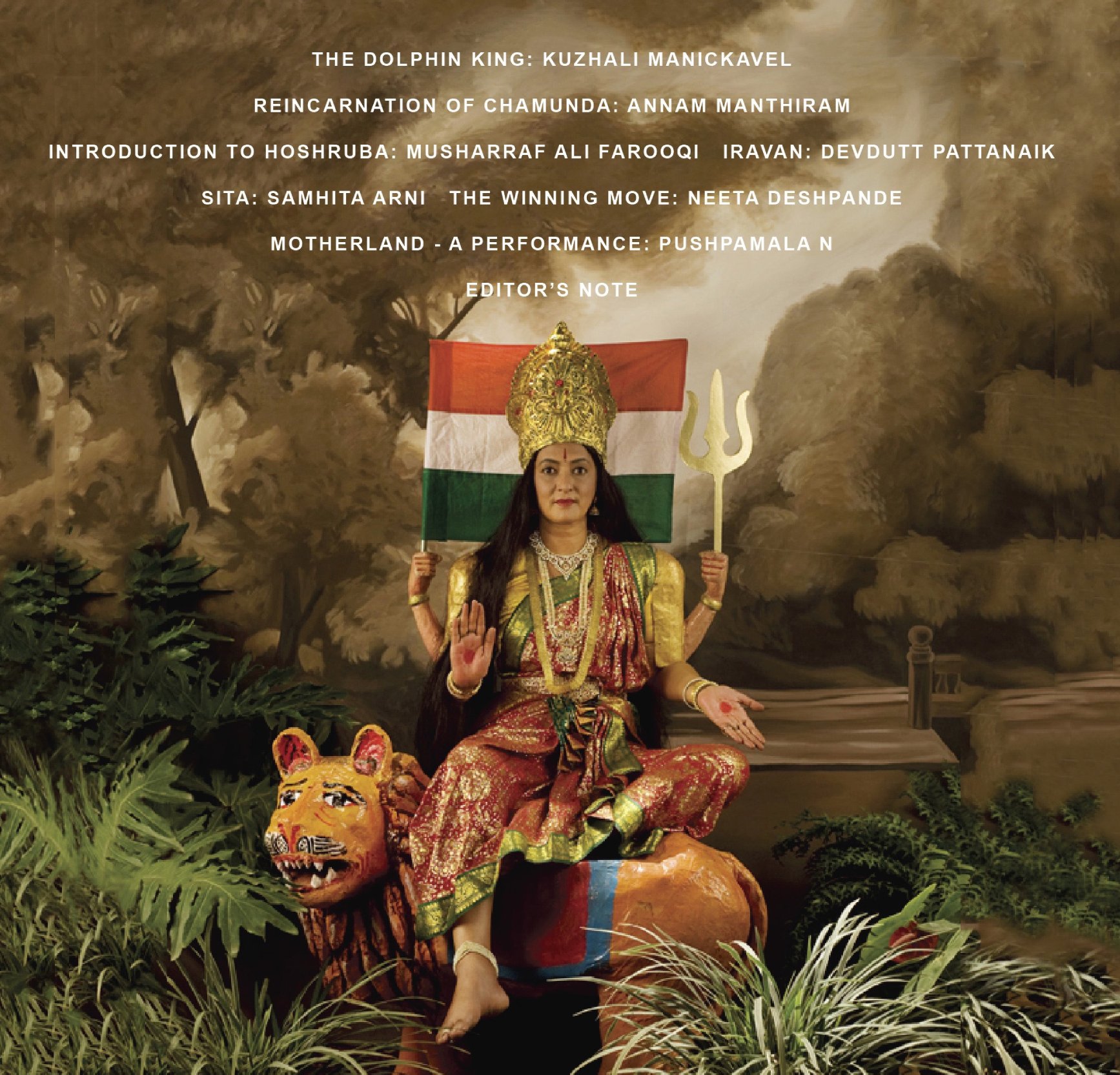

Art by Pushpamala N titled ‘Motherland – The Festive Tableau’, in studio photograph, photo credit: Clay Kelton, 2009.

Artwork - ISSUE 3

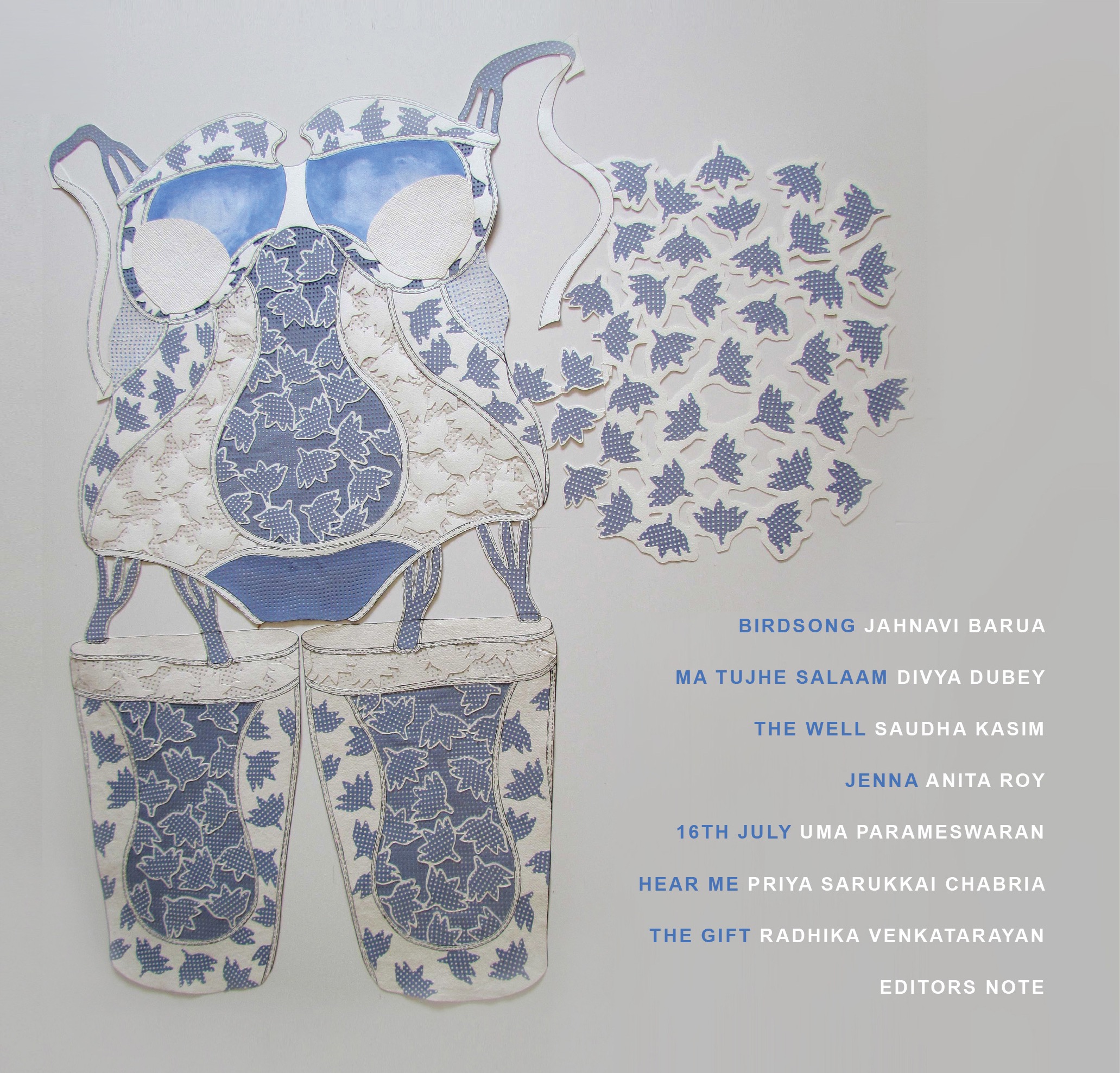

‘Worth the Weight’ by Nibha Sikander, collage with cut-out paper, 2010, part of a series on ‘the undergarment as a seductive yet empty metaphor for femininity’ executed while artist in residence at the American School of Bombay in a programme curated by Indira Chandrasekhar.

Artwork - ISSUE 2

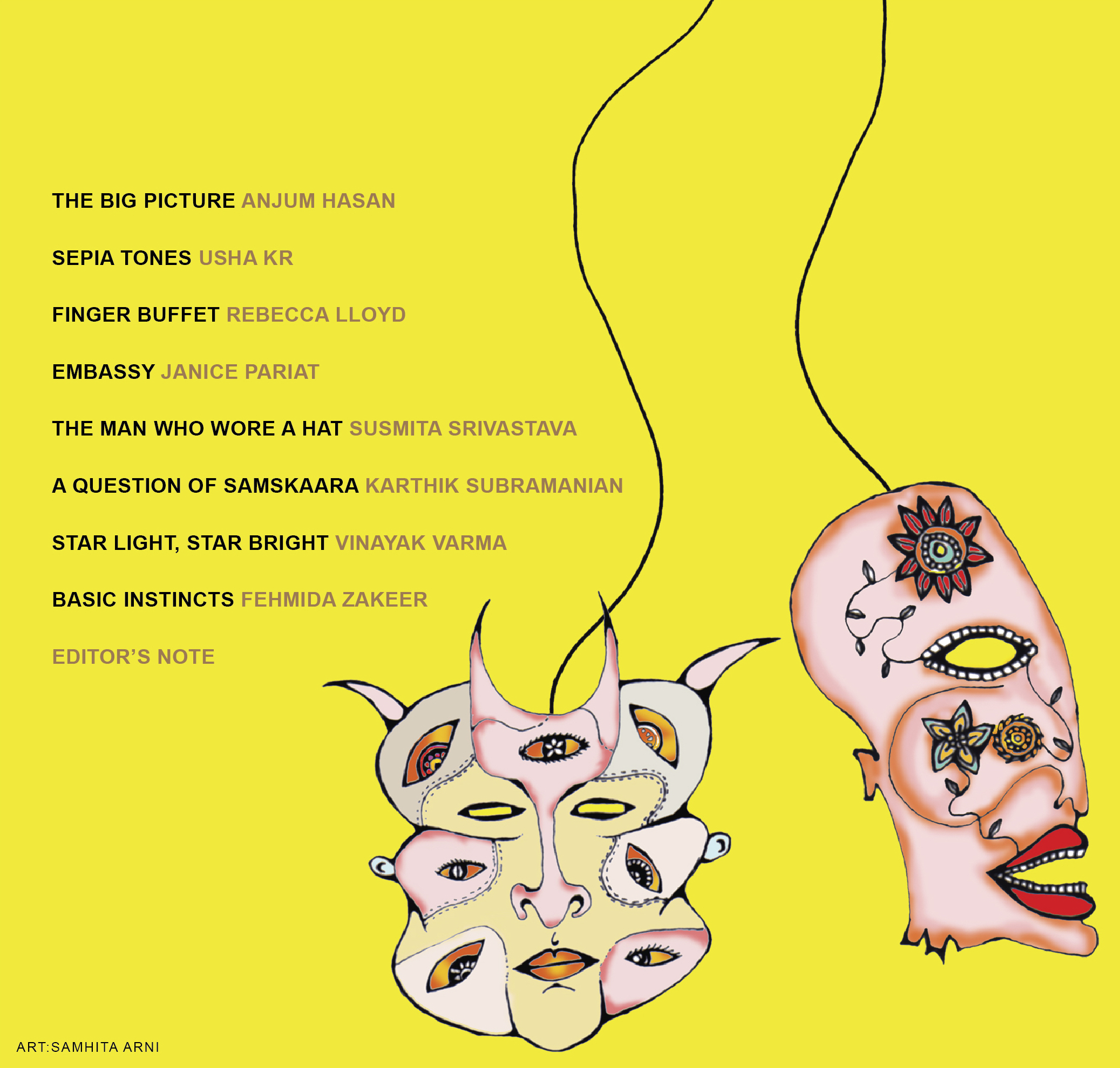

Art on the cover of Out of Print 2 is by our editor Samhita Arni and is titled ‘Masks’, digital art, 20011.

Artwork - ISSUE 1

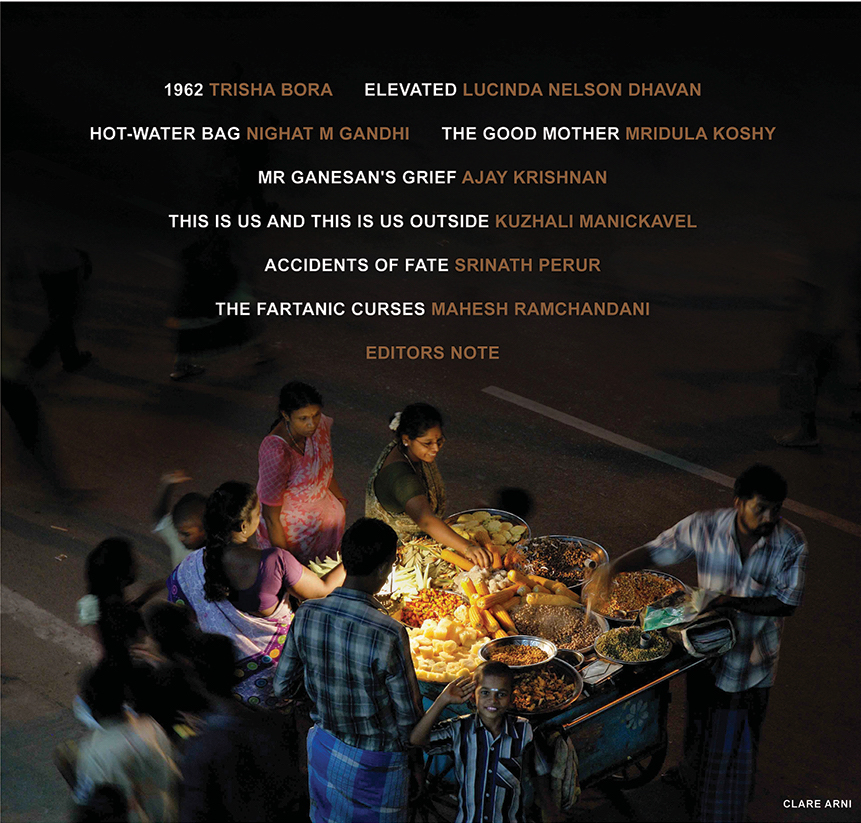

Photograph by Clare Arni taken during the Madurai Meenakshi Chitirai festival.